Behind Hakai: Nick Viner

A blog series highlighting the people who play an integral role behind the scenes to ensure the data keeps flowing and the Hakai Institute keeps running.

A person trained to map the ocean floor wouldn’t expect to find themselves working up in the sky or charting landslides along the largest river in British Columbia, but that’s precisely what happened to hydrographer Nick Viner since starting in his role with the Hakai Institute. Nick now takes on all sorts of exciting new challenges outside the realm of standard ocean-going hydrography, and everyone he works with is happy he sometimes ventures out of the ocean.

Started at Hakai

Spring 2018

Role

Hydrographer

Home Base

Victoria, BC

What do you do at the Hakai Institute?

I originally came on as a hydrographer, so someone whose skill set is involved with mapping the ocean floor using acoustics. It’s been something new every year, which has been great. My first year was essentially mapping the entire northwest coast of Calvert Island, which was a huge undertaking as my first project. Before that, I had about three or four years of hydrography under my belt, but going up to that field station [and being told] “all right Nick, here’s a boat, here’s a multibeam, map this whole thing” … oh boy.

When the airplane, the Airborne Coastal Observatory (ACO), started to pick up steam in 2020, a lot of my expertise in the marine side [was transferable]. Now a good chunk of my job is ACO involved because there’s so much more flying being done. Long story short, my job has expanded—which for me is super cool, to get to learn and get involved in all these things.

What got you into this kind of work?

I have a bachelor’s of science in psychology. My first few years of university I took everything—math, physics, psychology, religion—it was a mixing pot. In my third year, I took an astrophysics course, and we did this project where we went to the observatory, photographed a star over regular intervals, then brought the images back into a computer, processed them, and were able to graph the luminosity of the star over time. For me, that was amazing—this real-world data transferred into this digital form where we can, with our eyes, view what’s happening millions and millions of however many units of distance away. I’m from Nova Scotia, and Nova Scotia Community College has great programs for people with university degrees. I came across marine geomatics, and I had no idea what geomatics was, but the course description mentioned a lot of collecting data, and it was a one-year program—great! Let’s do that! I get there, and it’s all about surveying, acoustics, GPS positioning, setting up boats, and collecting data and bringing it back. After that, I got hired by a company down in Louisiana to do surveying, and then I applied to Hakai.

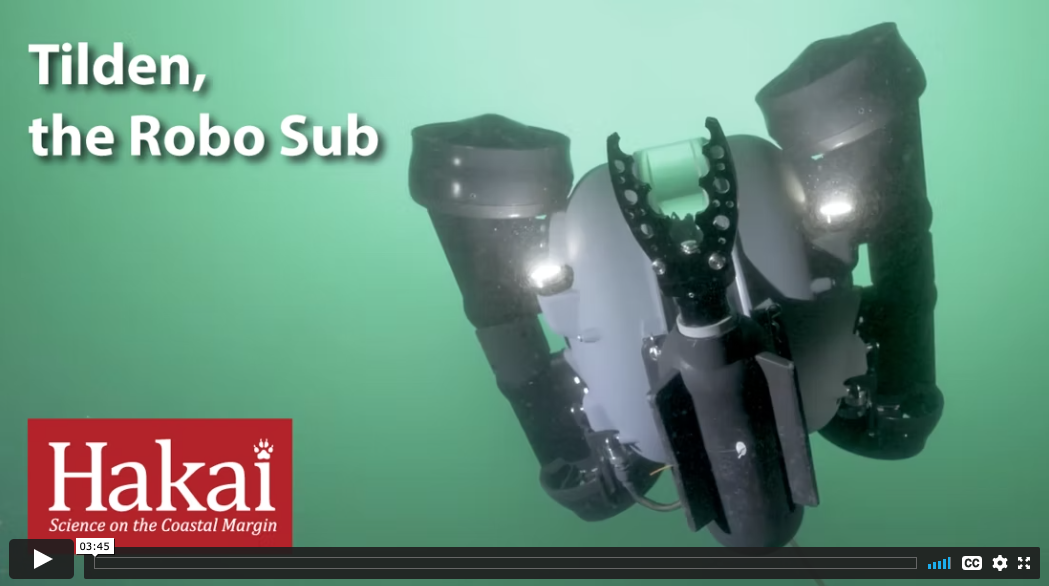

Nick Viner does a couple of big hydrography projects a year between his ongoing survey work with the Airborne Coastal Observatory. “I started doing hydrography—I love surveying the ocean, I love being in water.” Photo: a selfie with a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) deployed from Calvert Island. Video (click to watch): Nick’s work with the ROV is featured in “Tilden, the Robo Sub.”

What’s your favorite project you’ve worked on for Hakai?

It’s got to be the Fraser River project—“the big float”—though this might be a bit of recency bias. We’re doing multibeam surveys in the Fraser River through some canyons, which is cool because I helped to collect data from those canyons [in the ACO plane], and now I’m in those canyons, in this tiny pontoon boat, running through rapids and dodging icebergs in water that no one’s ever surveyed like this before. That was an amazing place to be, working very closely with Simon Fraser University (SFU) and their researchers and students, helping them out and providing guidance.

There were four of us on the boat: myself, a postdoc researcher from SFU, and two [Rivertec] boat operators: one to drive the boat and the other to be there just in case anything went wrong. Rivertec really made the whole thing happen: they have the expertise of the river to know where they could go and where they couldn’t, and they know how to operate the boat. It was almost all based on their local knowledge. That’s probably one of the reasons why folks who tried to survey there before just couldn’t get anything. Big shout-out to Rivertec!

It was everything I love and hate about hydrography all mashed into one. The plan was to map upstream and downstream of the Big Bar landslide. To get a boat upstream, Rivertec’s plan was to trailer it, put the boat in the water, and drive it down [to the start]. However, they discovered that there was still thick ice, and getting boats through was impossible. So they disassembled one of their boats into its component parts, deflated the pontoons, put it on a truck, and brought it downstream. We took that disassembled boat, drove it on another boat across the river, put each one of those parts on an ATV, drove those ATVs up past the landslide, reassembled the boat upstream, put a multibeam on it, and put it in the water. And everything worked—there were no issues!

Nick Viner runs a multibeam survey along a portion of the Fraser River from a small pontoon boat. “On that tiny boat there’s a little enclosure that’s just some metal beams and a tarp over it. I was in there, and had no idea what was going on outside,” says Nick. “When I’m looking at the multibeam and at the screen, I’m seeing a real-time view of the profile of the riverbed, and it shallows up really quickly, so from my view there’s not a whole lot of wiggle room in this very specific corridor. Then I look at that picture and think, There’s so much water! But most of that water is just somewhere you cannot put a boat, or else you run into these spires. Above water, you can see these spires that have been shaped over time, and those same things exist under the water.” First photo by Will McInnes, second photo by Nick Viner

Now we’re in these rapids, and there are icebergs coming down the river at us, so we have one guy calling out “iceberg” as we’re dipping and weaving trying to get as much data as we can. And this is the part I hate—we have this expensive piece of equipment in the water, and I’m thinking, Please do not let this thing hit anything, because I’ve got half a dozen researchers waiting on this data for their projects.

It was wild. There’s a lot of things that can go wrong in that kind of environment. In the open ocean, there’s always a chance that you could lose a sonar, and going from the well-charted open ocean to this relatively tiny chaotic river that’s never been charted before, I had to make it very clear: “You know there’s a chance we’re going to lose something here, right?” But everything worked out. We built an entire boat, we stuck the sensors on it, and we collected a lot of great powerful data with it. It’s been such a phenomenal experience.

How did that survey compare to others you’ve done?

Usually with a hydrographic survey, you have these standards you adhere to. But in this kind of environment, I essentially had to throw those out the window and make a new set of standards. Usually, you want to have the multibeam at least one meter below the waterline, so there’s no noise from aeration, but no, I was putting this thing right at the waterline because I don’t want to lose it! I had to, on the fly, make a bunch of calls that were outside the realm of what I would consider good practice in the ocean, but it worked in the river. I’m super proud of everyone I worked with and of the data that’s been collected.

What’s one aspect of the job you could do without?

I think everyone in this field of work can agree—we use very sensitive, delicate, and expensive pieces of equipment, so whenever you put that in the water, there’s always a risk. You could be in a boat in the Marianas Trench with the multibeam one meter below the waterline, and there’s still a chance that sensor is going to break. That’s the constant anxiety in the back of my head—are we going to get this sensor back, will we be able to complete the work? It’s not like everyone has a spare multibeam in their back pocket. Multibeams are essentially really sensitive speakers and microphones: you emit this pulse of sound that you could barely hear, and there’s this speaker trying to listen for that tiny pulse to return meters or hundreds of meters from the seafloor. If something were to smack it, you could easily blow something. I could do without that fear.

What’s your favorite glacier to survey?

Place Glacier, absolutely! We needed a candidate for testing out our hyperspectral camera. Place Glacier is smaller, it takes 45 minutes to collect, and it’s 30 minutes from the Victoria airport, so it was the perfect option. I’ve flown over it eight times now. It’s not like Klinaklini Glacier and the Columbia Icefields—these things are massive, and you’re up in the plane for 4–5 hours to get those! They’re fantastic, but Place Glacier is just this little glacier sitting just outside Pemberton. It holds a special place in my heart.

*This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.