WALL-E Returns to Shore for a Tune-Up

Plucking an ocean glider from the sea is anything but simple.

Ocean gliders lead a lonely life. Many of these marine robots spend months out at sea, diving to depths of 1,000 meters before returning to the surface. Only when they need a tune-up—a few times per year—is their solitary existence interrupted. But reunions, for gliders, can be dangerous.

“Gliders are great at surviving the ocean without breaking,” says James Pegg, a marine technician with Fisheries and Oceans Canada. “It is when they come in contact with people and boats that they are at risk.”

Just off Tofino, a 15-meter coast guard lifeboat putters along with a Zodiac in tow. The mountains of Vancouver Island fade into the distance as Pegg, Hakai’s Chris O’Sullivan, University of Victoria marine technician Cailin Burmaster, and members of the coast guard scan the seas for signs of “WALL-E”—a glider that’s due for pick up.

From her living room in Victoria over 150 kilometers away, Hayley Dosser remotely sends a message to WALL-E—named after the lonely trash compactor from the eponymous Pixar film—to keep the glider at the surface. Dosser, a postdoctoral researcher with the University of British Columbia, relays WALL-E’s GPS position to the recovery team until they can spot the yellow torpedo-shaped glider in the water.

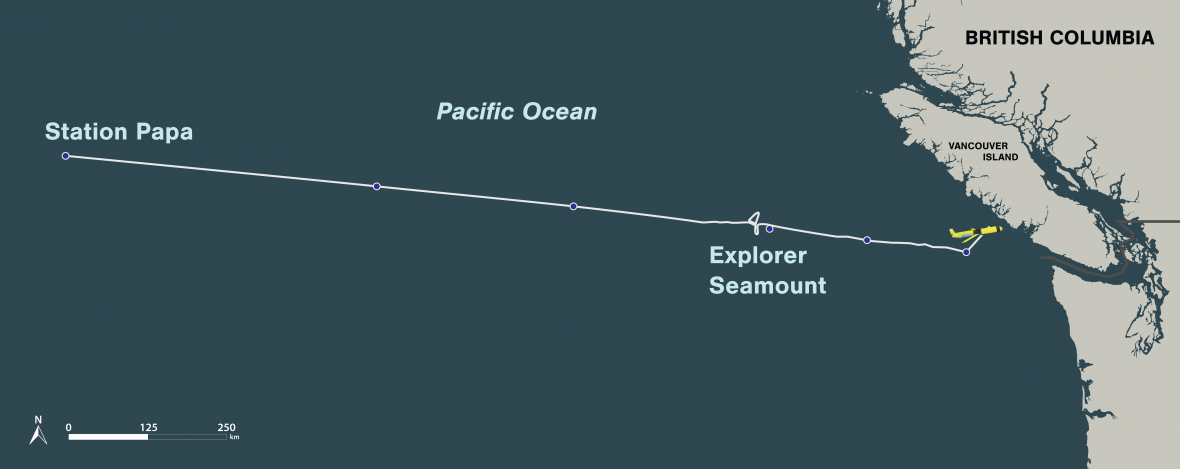

With some skillful boat maneuvering and human muscle, WALL-E successfully makes it into its specialized cart onboard the Zodiac. Besides a broken wing, WALL-E is in remarkably good shape given it’s spent three months at sea. In that time, the glider traveled over 2,600 kilometers to Station Papa and back—a distance akin to flying round trip between Vancouver and Regina.

WALL-E is part of an international fleet of gliders traveling the world’s oceans. Gliders collect invaluable data that helps scientists predict weather patterns, understand trends in fisheries, and track the effects of climate change.

With other important missions on the horizon, WALL-E’s time on shore is brief. The team has already fixed its wing, charged its batteries, and given it a tune-up all before it’ll be sent back to sea in early December for another months-long assignment along the same route.

“It’s simply not affordable to be out offshore with a ship all the time,” says Tetjana Ross, a research scientist with Fisheries and Oceans Canada. “But it is possible with a glider.”

For scientists, a glider’s alone time is invaluable.

Acknowledgements

This ocean glider research is part of the Canadian-Pacific Robotic Ocean Observing Facility, or C-PROOF—a collaboration between the University of Victoria, the University of British Columbia, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the Hakai Institute, and Ocean Networks Canada.