A Mud Shrimp’s Worst Nightmare

An invasive parasite is spreading up the coast of the Pacific Northwest.

Mud shrimp aren’t much to look at. Like crayfish but with stumpier claws, these homely crustaceans play an outsized role as essential engineers in the mudflats they call home. Mud shrimp cycle nutrients when they filter food, pumping oxygenated water into their tunnel dwellings, which also provide housing for a suite of other creatures. Their presence affects how the entire mudflat ecosystem functions, or doesn’t. But now, an invasive parasite threatens the mud shrimp’s future in British Columbia.

“I was on the lookout for things that seemed out of place,” says Matt Whalen, a Hakai postdoctoral researcher at the University of British Columbia who studies coastal biodiversity. “But this particular parasite wasn’t initially on my radar.”

Outbreaks of the parasite—a kind of isopod native to Asia—were first recorded on the Pacific coast of the United States in the 1980s and early 1990s. By the 2000s, it had reached as far north as Vancouver Island, British Columbia. And in 2017, Whalen and collaborators found the parasite had spread 300 kilometers farther north to Calvert Island on the Central Coast of British Columbia, as described in a publication in BioInvasions Records.

“It’s a bit depressing because we tended to associate this parasite with places that have a lot of marine traffic and aquaculture, like California and Oregon,” says Whalen. “Finding them on Calvert Island really suggests that there’s very little preventing the spread because of the parasite’s life cycle.”

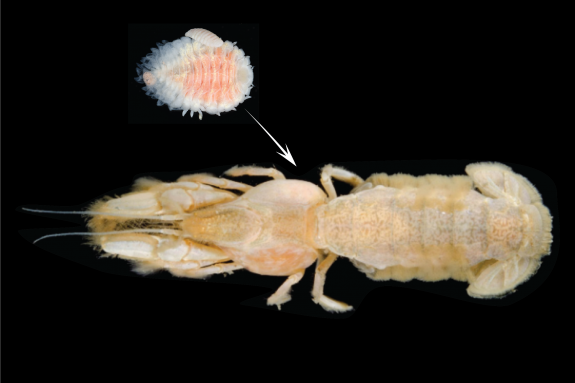

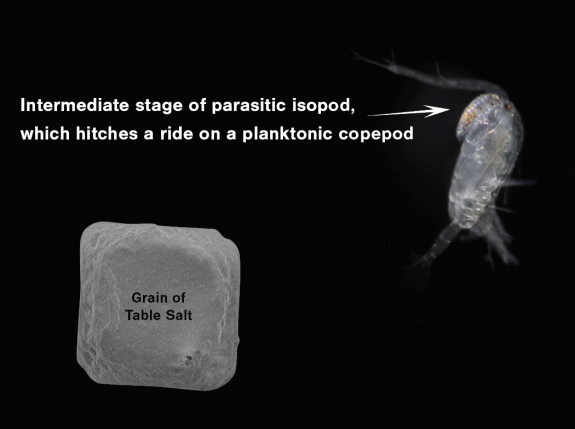

The parasite is a bizarre crustacean called a bopyrid isopod. In the pre-adult part of its life, the isopod hitches a ride on planktonic copepods—an intermediate host that allows the isopods to travel to new and far-flung mudflats in search of shrimp blood. As adults, bopyrids attach to the gills of another crustacean host, in this case a mud shrimp (Upogebia pugettensis), and proceed to sap the life from it. Infected mud shrimp are so hard done by that they lack the required energy to reproduce.

When a parasite coevolves in the same place as its host, they often reach a sort of detente. After all, the parasite needs a host to survive, and killing it off at once would not make a great long-term strategy. But when a parasite is introduced from elsewhere, that armistice may never arrive. Mud shrimp populations have collapsed from California to southern British Columbia, in large part because of how effective the Asian isopod is at castrating its host.

“The infection rates on Calvert Island were higher than I would’ve anticipated,” says Whalen. “About one in four hosts were parasitized. That’s a pretty good chunk of the population.”

For now, scientists are tracking the northward spread of the parasite. Whether mud shrimp populations collapse, and what effects that will have on the ecosystem are still unclear. The parasite’s prevalence on Calvert Island shows that it may only be a matter of time before it reaches the North Coast of British Columbia and moves onward to Alaska, the upper edge of the mud shrimp’s range. Northern mud shrimp beware.